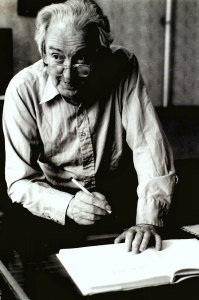

LAJOS SZALAY:

A REMEMBRANCE

By Charles Phipps

(http://muzsakkertjemiskolc.hu/)

Lajos Szalay was a black and white artist in a world of color. He liked to see life as either one way or the other — war or peace, sacrifice or redemption, or simply love or hate. He came to America after a long career of pointing this out to various programs of Nazi’s, Communists, and aging Peronists. Here, he found a strong belief in colorfulness, or at least shades of grayness, but became a spokesman for duality — in his mind, a uniquely Hungarian characteristic.

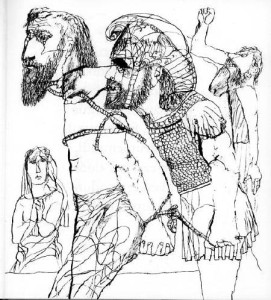

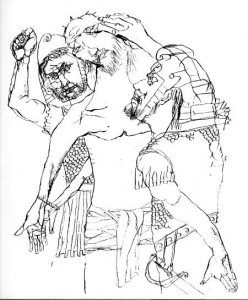

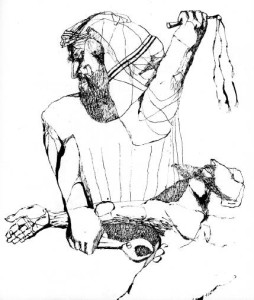

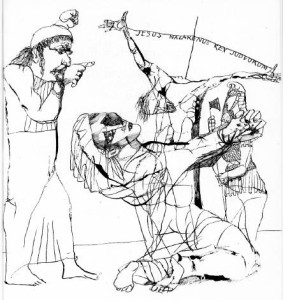

His work was confrontational, expressionistic and narrative. It almost always told a story, and that story was the black and whiteness of injustices that couldn’t be explained in shades of gray, or disguised by the facility of color — a very American viewpoint.

Szalay died this past April, 1995, at the age of 86, in Miskolc, Hungary, not far from the village of Őrmező where he was born, February 26, 1909. As a boy, he saw his father return in uniform from the Great War to find an artistically talented son with a gift for the acid tongue of language. Art won in the family battle, and he eventually graduated from the Fine Arts Academy in Budapest at age 26. He barely earned a living until making contact with István Farkas, the artist and publisher of Új Idők, as the new World War was about to erupt. He married his life-long partner, Júlia Hering, then also, in 1939.

He spent the war as an illustrator correspondent, and was sent to Paris by the new post-war Hungarian government to do more of the same at the Peace Conference of 1946. Unfortunately, the terror regime of the Soviets and Communists at home meant no return ticket, and Szalay stayed in France until 1948. Hen and Júlia emigrated to Argentina and enjoyed a successful career of teaching and exhibiting for the next 12 years. Their only child, Klára Mária, now known as Claire, was born in 1950 at the height of the popularity surrounding Eva Peron, while he was a professor of graphic art at the University of Tucuman. Az a Hungarian ex-patriot, he published a momentous collection of drawings about the events in Budapest of 1956 and, eventually, left-wing political backlash gave him the idea that it was time to leave, in 1960. The three departed on a ship out of Santiago, Chile, two days before an earthquake and tidal wave devastated the coastline, enjoyed a stopover in Havana, and landed in Boston.

A short time later, after settling in New York City, Szalay became a sought-after illustrator of books and articles but, in the decades of Pop and Minimalist Art, never attained a major gallery exhibition. As he said in 1970, “Only drawing suits the aesthetic asceticism I demand of myself.” Perhaps, the ascetic outlook of the poet, as well as his acerbic personality, kept him less than well known by all but the American-Hungarian community.

The pinnacle of his graphic art was probably reached with the publication of Genesis, in 1966, a unique collection of drawings inspired by the first book of the Old Testament, which was reprinted in Budapest, in 1973. The original idea for this creative outpouring came from Dorothy C. Wallace, of Boston, his first patron in America, and eventually came to fruition through the collaborative efforts of Andrew Hamza and many other Hungarian-Americans in the New York area. Although somewhat crudely reproduced, the drawings present a powerful statement of Szalay’s mastery of line, and the book is now a rare collector’s item. A dozen or so copies are being made available by his family, on the occasion of this event, for those collectors who may wish to purchase this singular achievement.

Lajos, Júlia and Klárika became American citizens in the mid-1960’s, and he made his first return visit to the homeland after 21 years, in 1967. With another immersion in Paris, in the early 1970’s, he returned to New York to produce what many critics believe are the strongest and most powerful works of art in his incredibly prolific artistic life. He produced numerous etchings that he personally pulled as monotypes, although the plates were never produced in editions. Collectors eagerly purchased the large-format drawings that flowed from his pen. Hundreds of drawings returned to Buenos Aires, where he was still famous, by the Argentine shipping magnate, Juan Tunica.

By 1984, he had effectively quit. Even though, a landmark exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, in 1980, and the presentation of the Magyar Népköztársaság Zászlórendje award, caused his fame in Hungary to increase. Every annual visit brought increasing recognition and financial acknowledgements and, in 1988, he and Juci néni returned for good — completing a circle for the French, Argentine, American who touched the Hungarian soul.

Szalay’s art has been written about so much, that we know he would feel pleased to be honored here among his American friends, and that this tribute is as much about what he did as an American as what all Hungarian-Americans have contributed to our society. Today’s program celebrating the memory of Lajos Szalay and the life of Béla Bartók is entirely fitting. He told William Juhász, in 1962, “I hear Bartók’s Hungarian vision with my blood and not with my ears — I can get lost in it.”

As we ponder the entrance of Jesus into the World, this Christmas season, perhaps the black and whiteness of Szalay’s art and the dis-jointed color of Bartók’s music can remind us of that unique thread of Hungarian spirit that winds its way throughout, not only America but, the Earth.

American Hungarian Museum, No. 39, 1995